Python Objects

工厂函数

就是指那些内建函数都是类对象,当调用他们时,实际上是创建了一个类实例。

#####变量定义

-

显示声明

C: 变量声明必须位于代码块最开始,且在任何其他语句之前。

C++、Java: 允许”随时随地”声明变量,不过仍必须在变量被使用前声明变量的名字和类型。 -

隐式

Python: 变量在第一次被赋值时自动声明。Python 是一种解释性语言,在创建(也就是赋值时),解释器会根据语法和右侧的操作数来决定新对象的类型。在创建对象后,一个该对象的应用会被赋值给左侧的变量。

内存分配

为变量分配内存时,是在借用系统资源,在用完之后,应该释放借用的系统资源。Python 解释器承担了此任务。

引用计数

Python 使用引用计数技术来保持追踪内存中的对象。当对象被创建时,便创建一个引用计数(每个对象各有多少个引用),当对象不在需要时(也即引用计数变为0时),它被垃圾回收。

dir() and del

>>> print dir.__doc__

dir([object]) -> list of strings

If called without an argument, return the names in the current scope.

Else, return an alphabetized list of names comprising (some of) the attributes

of the given object, and of attributes reachable from it.

If the object supplies a method named __dir__, it will be used; otherwise

the default dir() logic is used and returns:

for a module object: the module's attributes.

for a class object: its attributes, and recursively the attributes

of its bases.

for any other object: its attributes, its class's attributes, and

recursively the attributes of its class's base classes.

>>> dir()

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', '__package__']

>>> import sys

>>> dir()

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', '__package__', 'sys']

>>> del sys

>>> dir()

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', '__package__']

Reduce the Number of Lookups

To actually get the integer type object, the interpreter has to look up the types name first, and then within that module’s dictionary, find IntType. By using from-import, you can take away one lookup:

from types import IntType

if type(num) == IntType ...

Numbers

Type Categorized by the Update Model

| Update Model Category | Python Types That Fit Category |

|---|---|

| Mutable | List, dictionaries |

| Immutable | Numbers, strings, tuples |

Rather than referring to the original objects, new objects with the new values were allocated and (re)assigned to the original varibale names, and the old objects were garbage-collected. One can confirm this by using the __id()__ BIF(build-in function) to compare object identities before and after such assignments.

>>> dir()

['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', '__package__', 'foo', 'types', 'x']

>>> x

1

>>> id(x)

140457926481800

>>> x += 1

>>> id(x)

140457926481776

# a and b referring the same ...

>>> a = 10

>>> b = 10

>>> a is b

True

>>> id(a), id(b)

(140309388376016, 140309388376016)

>>> e = 10.0

>>> f = 10.0

>>> e is f

False

>>> id(e), id(f)

(140309388384736, 140309388384760)

>>> s = 0.0

>>> for i in range(10):

... s += 0.1

...

>>> s

0.9999999999999999

>>> print s

1.0

Notice how for each change, the ID for the list remained the same.

>>> list

['this', 5, 'list']

>>> id(list)

4303214496

>>> list[0] = 'list'

>>> list

['list', 5, 'list']

>>> id(list)

4303214496

>>>

Factory functions, just means that those objects are now classes, and when you “call” them, you are just creating an instance of that class.

Compare

- int(): chops off the decimal point and everything after. 直接截去小数部分(返回值为整型)

- floor(): rounds you to the next smaller integer, i.e., the next integer moving in a negative direction(toward the left on the number line). 得到最接近原数但小于原数的整型。

-

round(): (round zero digits) rounds you to the nearest integer period. 得到最接近原数的整型。

>>> print hex.__doc__ hex(number) -> string Return the hexadecimal representation of an integer or long integer. >>> print oct.__doc__ oct(number) -> string Return the octal representation of an integer or long integer. >>> >>> hex(255) '0xff' >>> oct(255) '0377' >>> print chr.__doc__ chr(i) -> character Return a string of one character with ordinal i; 0 <= i < 256. >>> print ord.__doc__ ord(c) -> integer Return the integer ordinal of a one-character string. >>> chr(99) 'c' >>> ord('d') 100

Sequences: strings, Lists, and Tuples

Sequence type all share the same access model: ordered set with sequentially indexed offsets to get to each element. Multiple elements may be selected by using the slice operators.

Repetition

The repetition operator is useful when consecutive copies of sequence elements are desired. The syntax for using the repetition operator is as follows:

#sequence * copies_int

>>> '*' * 40

'****************************************'

>>> 'what!' * 4

'what!what!what!what!'

The number of copies, copies_int, must be an integer. As with the concatenation operator, the object returned is newly allocated to hold the contents of the multiply replicated objects.

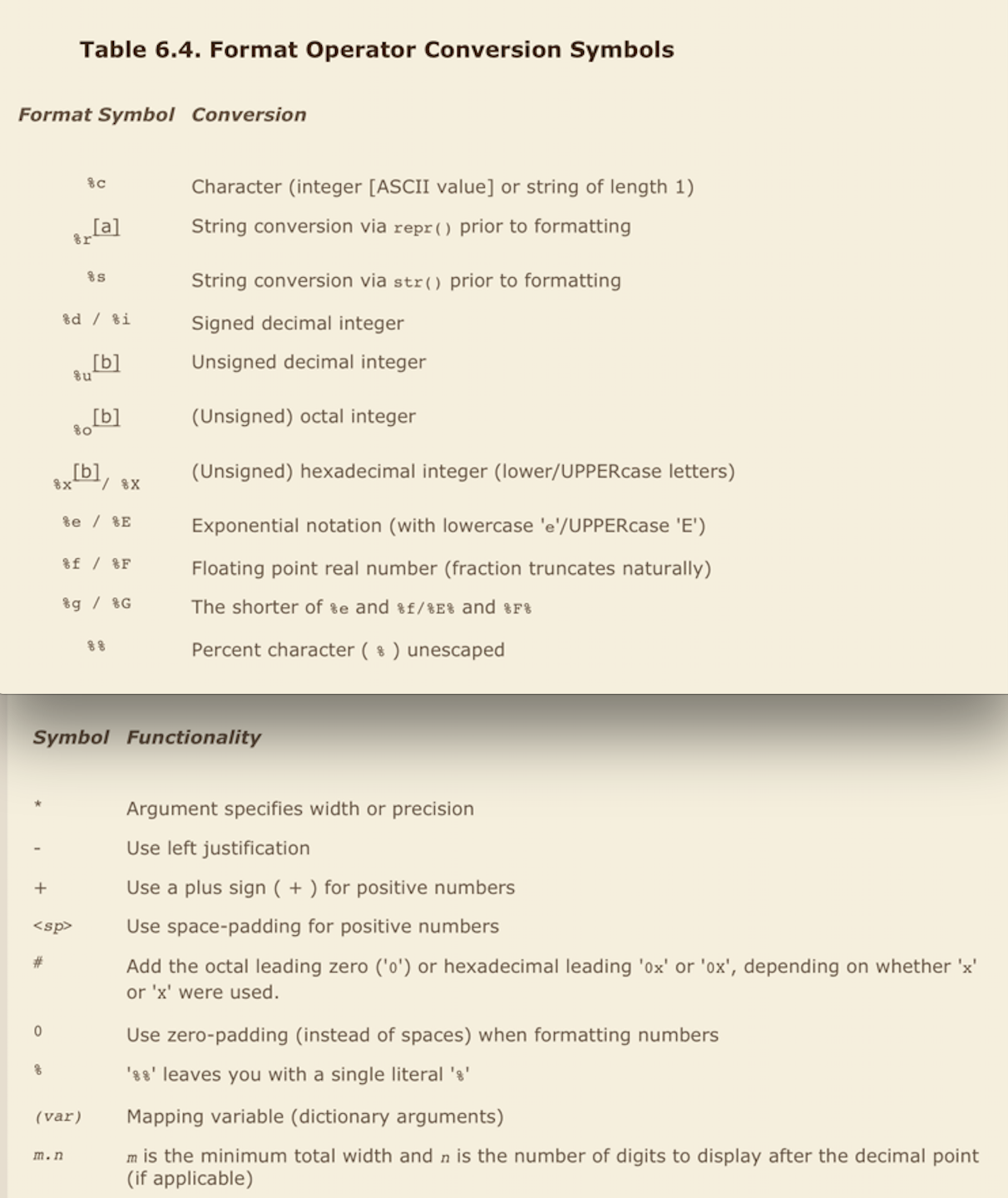

Format Operator (%)

Special Features of Lists

** Cerating Other Data Structures Using Lists **

- Stack: A last-in-first-out (LILO) data structure.

- Queue: A first-in-first-out (FIFO) data structure, which works like a bank teller line. The first person in line is the first one served. New elements join by being “enqueued” at the end of the line, and elements are removed from the front by being “dequeued.”

- Tuples: Tuples are another container type extremely similar in nature to lists. The only visible difference between tuples and lists is that tuples use parentheses and lists use square brackets. and Tuples are immutable, Because of this, tuples can do something that lists cannot do…be a dictionary key. Tuples are also the default when dealing with a group of objects.

Sidle-Element Tuples: to place a trailing comma (,) after the first element to indicate that this is a tuple and not a grouping.

>>> type( ('xyz') )

<type 'str'>

>>> type( ('xyz',) )

<type 'tuple'>

Dictionary Keys

Immutable objects have values that cannot be changed. That means that they will always hash to the same value. This is the requirement for an object being valid dictionary key. As we will find out in the next chapter, keys must be washable objects, and tuples meet that criteria. Lists are not eligible.

Lists & Tuples

list() and tuple() are functions that allow you to create a tuple from a list and vice versa( vice versa means ‘反之亦然’). When you have a tuple and want a list because you need to update its objects, the list() function suddenly becomes your best buddy. When you have a list and want to pass it into a function, perhaps API, and you do not want anyone to mess with the data, the tuple() function comes in quite useful.

>>> tuple([1, 2, 3])

(1, 2, 3)

>>> list((4, 5, 6))

[4, 5, 6]

Size

a = tuple(range(1000))

b = list(range(1000))

a.__sizeof__() # 8024

b.__sizeof__() # 9088

Due to the smaller size of a tuple operation with it a bit faster but not that much to mention about until you have a huge amount of elements. Permitted operations

b = [1,2]

b[0] = 3 # [3, 2]

a = (1,2)

a[0] = 3 # Error

sxdcfm, that also mean that you can't delete element or sort tuple. At the same time you could add new element to both list and tuple with the only difference that you will change id of the tuple by adding element

a = (1,2)

b = [1,2]

id(a) # 140230916716520

id(b) # 748527696

a += (3,) # (1, 2, 3)

b += [3] # [1, 2, 3]

id(a) # 140230916878160

id(b) # 748527696

Usage

You can’t use list as a dictionary identifier

a = (1,2)

b = [1,2]

c = {a: 1} # OK

c = {b: 1} # Error

Copying python objects and Shallow and Deep Copies

A shallow copy is where only references are copied…no new objects are made! If you also want copies of the objects(including recursively if you have container objects in containers), you will need to learn about deep copies.

The shallow and deep copy operations that we just described are found in the copy module. There are really only two functions to use from this module: copy() creates shallow copy, and deepcopy() creates a deep copy.

Append

>>> import string

>>> string.letters

'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

>>> string.digits

'0123456789'

>>> import keyword

>>> keyword.kwlist

['and', 'as', 'assert', 'break', 'class', 'continue', 'def', 'del', 'elif', 'else', 'except', 'exec', 'finally', 'for', 'from', 'global', 'if', 'import', 'in', 'is', 'lambda', 'not', 'or', 'pass', 'print', 'raise', 'return', 'try', 'while', 'with', 'yield']

>>>

Mapping and Set Types

Dictionary may be created using a very convenient built-in-method for creating a “default” dictionary whose elements all have the same value(default to None if not given), fromkeys():

>>> ddict = {'x': 'hello', 'y': 'dict'}

>>> fdict = {}.fromkeys(('m', 'n'), 8)

>>> edict = {}.fromkeys(('foo', 'bar'))

>>> print ddict, fdict, edict

{'y': 'dict', 'x': 'hello'} {'m': 8, 'n': 8} {'foo': None, 'bar': None}

Core TIps

Because dict() is now a type and factory function, overriding it may cause you headaches and potential bugs. The interpreter will allow such overriding-hey, it thinks you seem smart and look like you know what you are doing! So be careful. Do NOT use variables named after built-in types like: dict, list, file, bool, str, input, Or len!

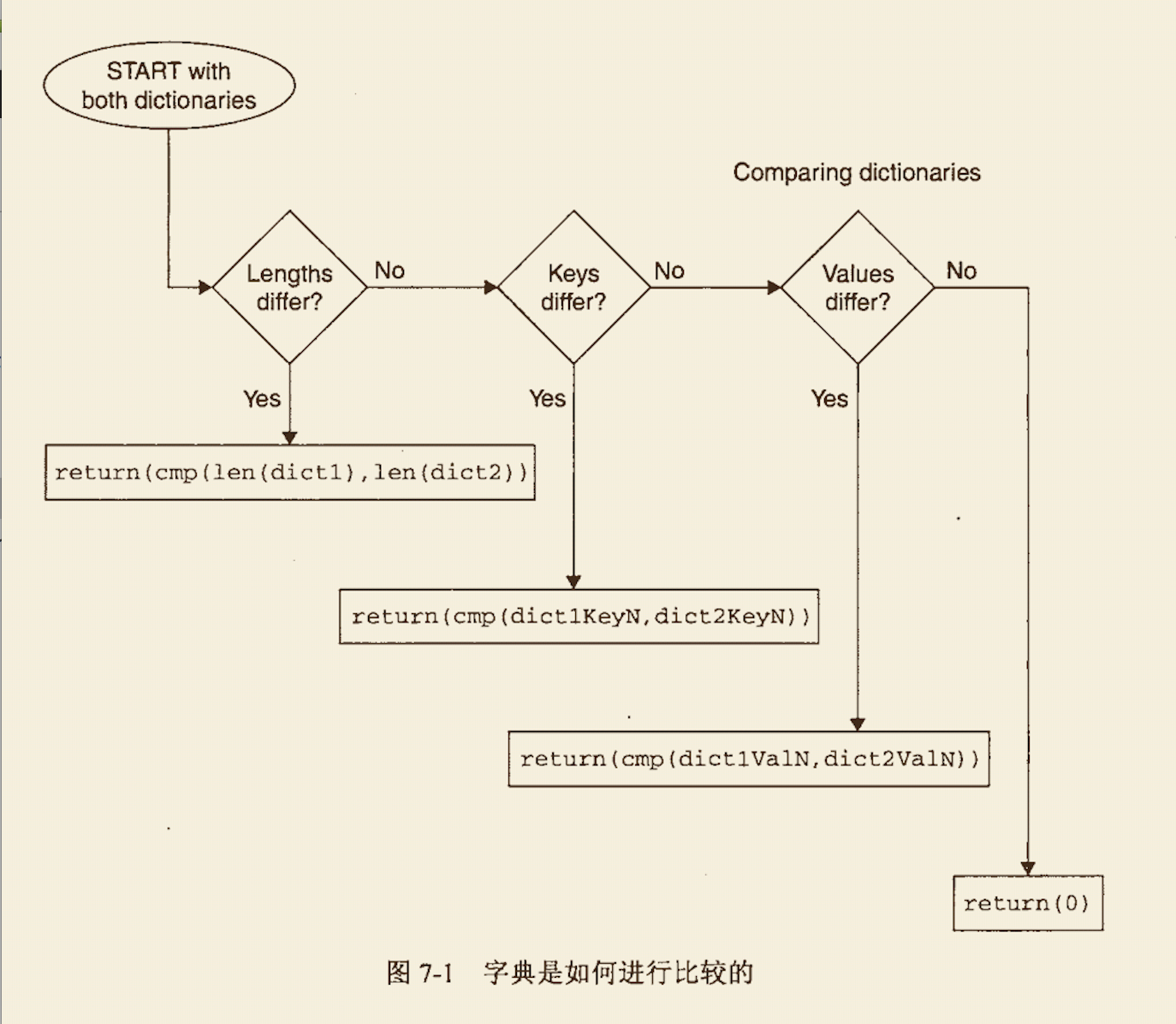

How dictionaries are compared

Functions and Functional Programming

Non-keyword Variable Arguments (Tuple)

A **TypeError exception is generated whenever an incorrect number of arguments is given in the function invocation. By adding a variable argument list variable at the end, we can handle the situation when more than enough arguments are passed to the function because all the extra(non-keyword) ones will be added to the variable argument tuple.

>>> def tupleVariable(arg1, arg2='defaultB', *theRest):

... 'display regular args and non-keyword variable args'

... print 'format arg 1: ', arg1

... print 'format arg 2: ', arg2

... for eachXtrArg in theRest:

... print 'another arg: ', eachXtrArg

...

>>> tupleVariable('abc')

format arg 1: abc

format arg 2: defaultB

>>> tupleVariable(23, 4.56)

format arg 1: 23

format arg 2: 4.56

>>> tupleVariable('abc', 123, 'xyz', 456.789)

format arg 1: abc

format arg 2: 123

another arg: xyz

another arg: 456.789

Keyword Variable Arguments (Dictionary)

In the case where we have a variable number or extra set of keyword arguments, these are placed into a dictionary where the “Keyword” argument variable names are the keys, and the arguments are their corresponding values. A double asterisk (**) is used.

>>> def dictVarArgs(arg1, arg2='defaultB', **theRest):

... 'display 2 regular args and keyword variable args'

... print 'format arg1: ', arg1

... print 'format arg2: ', arg2

... for eachXtrArg in theRest.keys():

... print 'Xtr arg %s: %s' % (eachXtrArg, str(theRest[eachXtrArg]))

...

>>> dictVarArgs(1220, 740.3, c='grail')

format arg1: 1220

format arg2: 740.3

Xtr arg c: grail

>>> dictVarArgs(arg2='tales', c='grail', d=123, arg1='mystery')

format arg1: mystery

format arg2: tales

Xtr arg c: grail

Xtr arg d: 123

>>> dictVarArgs('one', d=10, c='grail', e='zoo', men=(123, 'fuck'))

format arg1: one

format arg2: defaultB

Xtr arg c: grail

Xtr arg men: (123, 'fuck')

Xtr arg e: zoo

Xtr arg d: 10

Modules

####Search Path

>>> import sys

>>> sys.path

['', '/Library/Python/2.7/site-packages/virtualenv-15.0.2-py2.7.egg', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python27.zip', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7']

>>> type(sys.path)

<type 'list'>

Bearing in mind that is just a list, we can definitely take Liberty with it and modify it at our leisure. If you know of a module you want to import, yet its directory is not in the search path, by all means use the list’s append() method to add it to the path, like so:

>>> import os

>>> os.getcwd()

'/Users/xing'

>>> sys.path.append(os.getcwd())

>>> sys.path

['', '/Library/Python/2.7/site-packages/virtualenv-15.0.2-py2.7.egg', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python27.zip', '/System/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7', '/Users/xing']

####Import Modules

It is recommended that all imports happen at the top of Python modules. Furthermore, imports should follow this ordering:

- Python Standard Library modules

- Python third party modules

- Application-specific modules

Separate these groups with an empty line between the imports of these types of modules. This helps ensure that modules are imported in a consistent manner and helps minimize the number of import statements required in each of the modules.

Instance Attributes

Being able to create an instance attribute “on-the-fly” is one of the great features of Python classes, initially (but gently) shocking those coming from C++ or Java in which all attributes must be explicitly defined/ declared first.

Python is not only dynamically typed but also allows for such dynamic creation of object attributes during run-time. It is a feature that once used may be difficult to live without. Of course, we should mention to the reader that one much be cautious when creating such attributes.

One pitfall is when such attributes are created in conditional clauses: if you attempt to access such an attribute later on in your code, that attribute may not exist if the flow had not entered that conditional suite. The moral of the story is that Python gives you a new feature you were not used to before, but if you use it, you need to be more careful, too.

####Functions versus methods

Methods are basically functions but tied to a specific class object type. They are defined as part of a class and are executed as part of an instance of that class.